Fernando Abdalla, Mathilde Daheron and Eloy Vicente

Health Affairs & Policy Research, Weber Health Economics & Market Access, Weber Data & Technology, Weber

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare systems across Europe are increasingly turning to value-based healthcare models as a strategic framework to improve patient outcomes within the constraints of finite resources. Although promising in concept, the implementation of such models presents challenges in the context of complex, longterm conditions such as rare diseases. These conditions often involve diagnostic uncertainty, fragmented care pathways, and a lack of standardized metrics to assess health outcomes

and service quality. This complexity complicates the assessment of the true value delivered to patients, particularly in multidisciplinary envi- ronments where care spans multiple levels of the health system1,2.

Rare diseases, by their very nature, affect small patient populations, which makes traditional clinical trials difficult to conduct and limits the availability of robust evidence

on safety, efficacy, and long-term benefit. For these reasons, orphan drugs—therapies developed specifically to treat rare conditions— tend to carry a higher degree of

uncertainty at the time of market access. As a result, they often pose significant challenges for health authorities tasked with making reimbursement decisions based on incomplete data. The economic impact of these treatments is also considerable, as many orphan

drugs are associated with very high costs per patient, placing additional pressure on already strained healthcare budgets3-7.

Traditionally, pricing and reimbursement decisions for orphan drugs have relied on setting maximum prices based on expected therapeutic benefit, target population, and novelty, among other factors. However, in recent years, payers and manufacturers have sought

more adaptive and risk-mitigating approaches. The absence of «perfect information»—particularly in terms of long-term clinical outcomes and real-world effectiveness—

has driven interest in outcome-based payment (OBP) models. These agreements aim to link payment to actual health outcomes or financial performance, offering a more

dynamic and evidence-informed pathway to reimbursement. This is especially relevant for high cost treatments where traditional cost-effectiveness frameworks may not be adequate to capture value8,9.

In this context, technology is emerging as a critical enabler of OBP models, offering tools to

design, implement, and monitor these agreements with greater transparency and precision. From real-world data platforms to artificial intelligence and digital registries, technological innovation is helping to reduce uncertainty, support outcome measurement, and facilitate coordination between stakeholders. The objective of this article is to analyze how technological solutions are being applied to the design, implementation, and monitoring of OBP agreements for orphan drugs and advanced therapies, highlighting their role in improving transparency, efficiency, and sustainability in drug financing.

To this end, the article will begin with a theoretical overview of shared risk and outcome-based models, followed by an analysis of current OBP agreements internationally.

It will then focus in detail on real-world examples of where technology has played a central role, before discussing the challenges and opportunities in this area, and concluding with recommendations for healthcare systems.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: SHARED RISK AGREEMENTS AND OUTCOME-BASED

PAYMENTS

Definitions

Shared Risk Agreements (SRAs) and OBP models have emerged as pivotal contractual frameworks that distribute financial and clinical uncertainties between payers and

pharmaceutical manufacturers. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they encapsulate nuanced differences. SRAs encompass a broader spectrum of arrangements, including those based on both financial and clinical performance outcomes. OBP models, a subset of SRAs, specifically refer to agreements where the final payment is explicitly tied to the achievement of predefined health outcomes in real-world clinical settings10.

The essence of these models could be encapsuled by the following definition:

OBP Agreements are structured reimbursement contracts between healthcare payers and pharmaceutical manufacturers that condition all or part of the financial transaction on the achievement of clinical or health system outcomes, with the objective of reducing uncertainty, improving accountability, and aligning value delivery with actual patient benefit11.

OBP models differ from traditional pricing approaches by incor- porating real-world performance metrics into reimbursement structures. Under these models, a treatment’s effectiveness is monitored within a defined patient group over a specific timeframe, and future reimbursement is tied to the clinical and economic outcomes achieved. OBPs are designed to meet the growing need for transparency, flexibility, and evidence-based decisions particularly as many high-cost treatments, like orphan drugs, are launched with limited long-term data on their efficacy10.

Types of Agreements

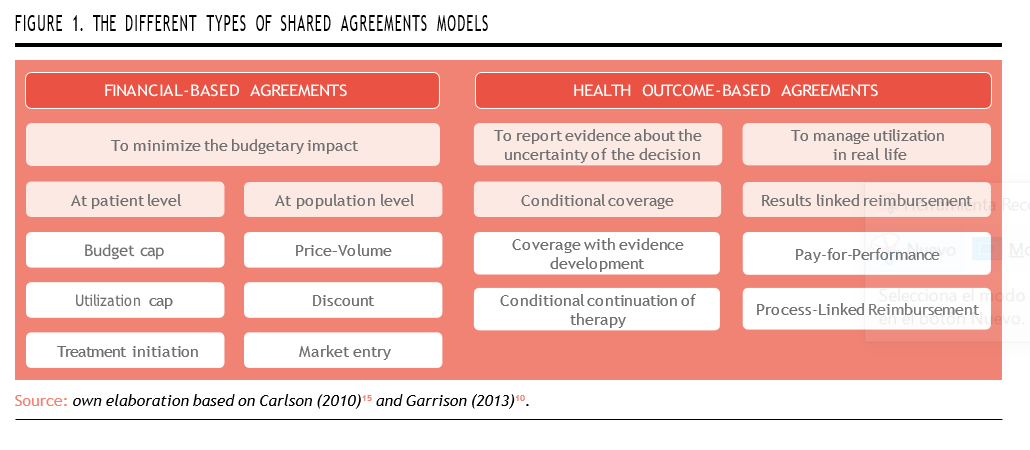

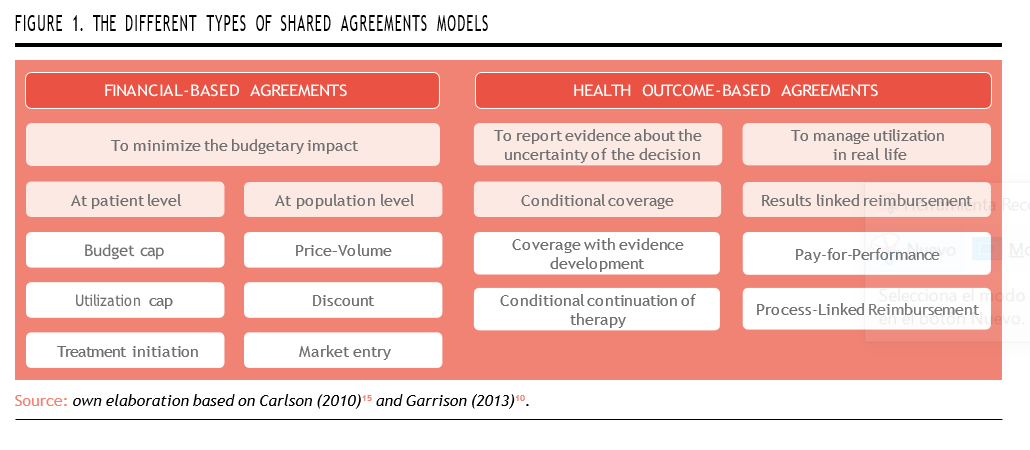

Outcome-based models can be broadly categorized into two primary groups, based on the nature of uncertainty they aim to mitigate, and the metrics employed to define success.

Financial-Based Agreements

These agreements primarily focus on minimizing the budgetary impact and ensuring cost containment when adopting new, often expensive therapies. The outcomes measured are financial rather than clinical, aiming to make expenditures more predictable.

Key types of financial-based agree- ments include12:

- Price-Volume Agreements: These link the price of a drug to the volume purchased. As volume increases, the unit price may decrease, thus mitigating excessive financial exposure due to overuse.

- Discount Schemes and Rebates: These arrangements offer fixed or tiered price reductions, ensuring affordability without evaluating clinical outcomes.

- Budget/Utilization Caps: These set a maximum cumulative expenditure or dose level. Costs beyond the agreed limit are absorbed by the manufacturer.

- Treatment Initiation Agreements: The manufacturer covers initial treatment cycles until sufficient data justifies full reimbursement.

- Market Entry Agreements: Temporary price reductions are offered to accelerate market uptake, often in exchange for faster access or wider patient inclusion.

While effective in stabilizing financial risk, these models do not directly incentivize real-world clinical performance or health system efficiency. They are generally easier to implement but less aligned with VBHC principles.

Health Outcome-Based Agreements

These models represent the core of OBP strategies and are designed to link reimbursement to actual clinical outcomes experienced by patients in real-world settings. They address clinical uncertainty, which is particularly pronounced in the case of orphan drugs due to limited trial populations and short study durations.

Key types of health outcome-based agreements include12:

- Pay-for-Performance: The most emblematic model of OBP, these agreements stipulate that payment is contingent on achieving specific clinical For instance, reimbursement may depend on a drug achieving survival, disease remission, or biomarker targets. If the drug fails to meet those thresholds, the manufacturer must provide rebates, discounts, or reimburse the cost. Their success depends on having robust outcome metrics, consistent patient monitoring, and a data infrastructure that supports longitudinal analysis.

- Conditional Continuation of Therapy: Under these models, the continuation of coverage for a given patient is based on short term response milestones. Only those who demonstrate early benefit are allowed to continue This minimizes unnecessary spending and ensures clinical appropriateness at the individual level.Coverage with Evidence Development: Reimbursement is granted conditionally, requiring the manufacturer to collect additional real-world evidence (RWE) post- This may involve observational studies, registries, or ongoing trials. This model provides earlier access while reducing long-term risk, and it’s often used in situations with accelerated regulatory approvals.

- Process-Linked Reimbursement: These less common agreements reimburse a product based on its impact on the broader care pathway. For example, a diagnostic test might be reimbursed based on its ability to reduce downstream treatments or hospital While more typical for medical devices, this logic can be applied to stratification tools used with high-cost drugs.

In the context of orphan drugs, health outcome-based agreements are especially pertinent due to the unique characteristics of these treatments8,13:

- High cost and limited patient populations make cost-effectiveness highly variable across individuals.

- A high degree of clinical uncertainty—stemming from small clinical trials, heterogeneous responses, and limited generalizability of results— which makes evidence-based decision-making more difficult.

- Lack of long-term data at market entry increases risk for payers.

- Need for early access compels regulators and health systems to approve reimbursement based on limited evidence.

By linking reimbursement to patient results, OBP models offer a pragmatic path to access while ensuring ongoing evaluation. However, they are also more demanding: they require data capture infrastructure and increased administrative burden, welldefined outcomes, collaboration across stakeholders, and often third-party validation (Figure 1)14.

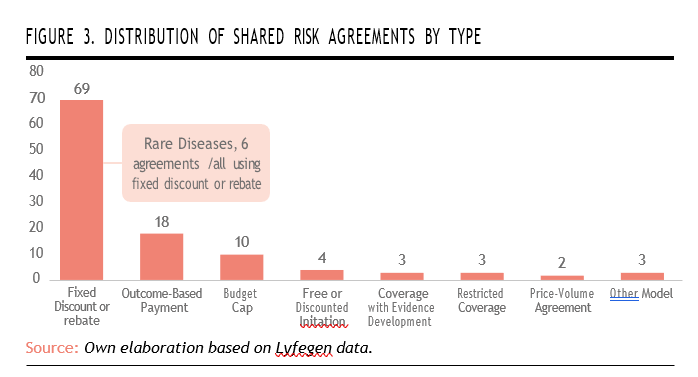

CURRENT LANDSCAPE OF OUTCOME-BASED PAYMENT AGREEMENTS: GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES

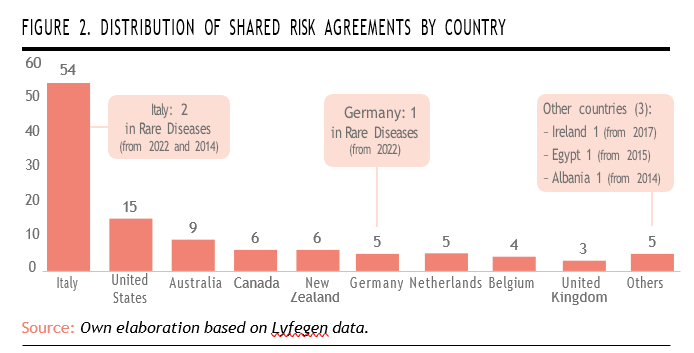

Before exploring concrete examples of technological integration into OBP models, it is essential to examine the current landscape of OBP agreements globally. This provides contextual understanding of where such agreements are most prevalent, and what types are being adopted.

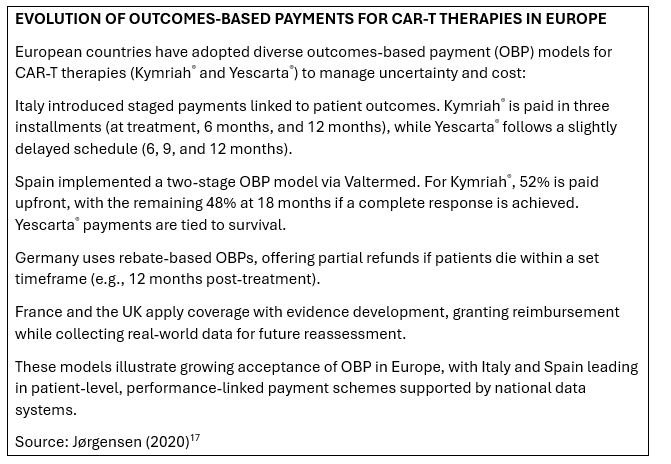

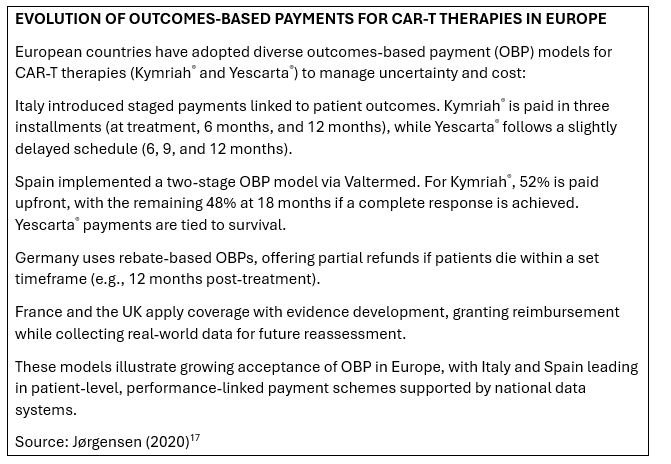

The following descriptive analysis is based on a database compiled by Lyfegen16, a company that collaborates with the Weber Foundation, publishers of newsRARE magazine. The dataset includes publicly available information on 153 OBP agreements implemented between 2008 and December 2023 (up to December 2022 in the case of Spain). Of these, 41 agreements were concluded in Spain (excluded from the current analysis), while the remaining 112 were executed across fourteen other countries. The agreements vary in nature, encompassing both financial-based and clinical outcome-based models.

According to the analyzed data, Italy leads with the highest number of OBP agreements globally, totaling 54. It is followed by the United States (15 agreements), Australia (9), and New Zealand (6). This distribution illustrates that OBP models have been adopted across a diverse set of countries, regardless of population size or the structural characteristics of their healthcare systems.

When focusing specifically on rare diseases, the data reveals a more limited adoption of OBP agreements across select countries. Italy stands out as the most active, having implemented two agree- ments related to rare diseases, one in 2022 and another in 2014; howe- ver, these represented only 4% of the total OBP agreements imple- mented in the country during the period. Germany follows with one rare disease agreement initiated in 2022. Among the group of «other countries,» three nations have each introduced a rare disease-focused OBP agreement: Ireland (2017), Egypt (2015), and Albania (2014). While these numbers are modest relative to total OBP activity, they highlight growing international willingness to apply performance-based approaches in the high-uncertainty context of rare disease treatments (Figure 2).

When focusing specifically on rare diseases, the data reveals a more limited adoption of OBP agreements across select countries. Italy stands out as the most active, having implemented two agree- ments related to rare diseases, one in 2022 and another in 2014; howe- ver, these represented only 4% of the total OBP agreements imple- mented in the country during the period. Germany follows with one rare disease agreement initiated in 2022. Among the group of «other countries,» three nations have each introduced a rare disease-focused OBP agreement: Ireland (2017), Egypt (2015), and Albania (2014). While these numbers are modest relative to total OBP activity, they highlight growing international willingness to apply performance-based approaches in the high-uncertainty context of rare disease treatments (Figure 2).

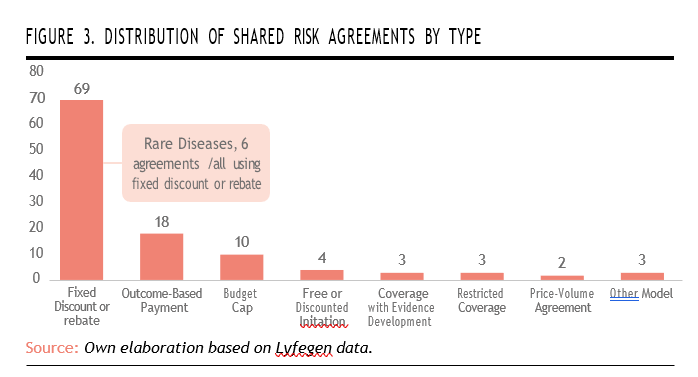

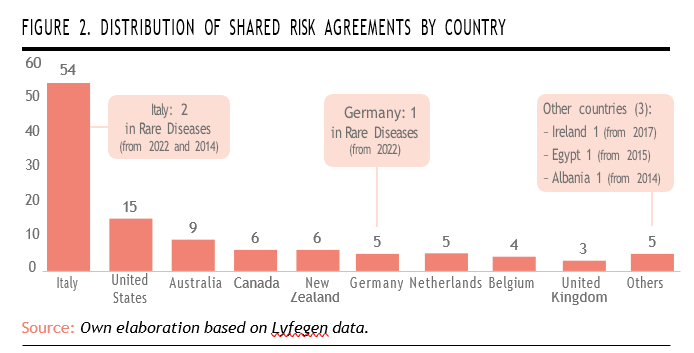

The analysis also reveals a clear predominance of financial-based agreements (such as fixed discount or rebate schemes), totaling 69 agreements, which represents 62% of the total. OBP agreements rank second, with 18 agreements.

When it comes to rare diseases, the data shows that these conditions remain underrepresented within outcome-based frameworks. All of the agreements in rare diseases relied exclusively on fixed discount or rebate models. This suggests that while rare diseases are starting to be included in risk-sharing schemes, they are still largely managed through simpler, financially-oriented mechanisms. The absence of outcome-based models in this category highlights a missed opportunity to better align reimbursement with clinical benefit, particularly given the high uncertainty and cost associated with orphan drugs. It also points to the continued need for robust data infrastructure and outcome measurement tools tailored to rare disease contexts (Figure 3).

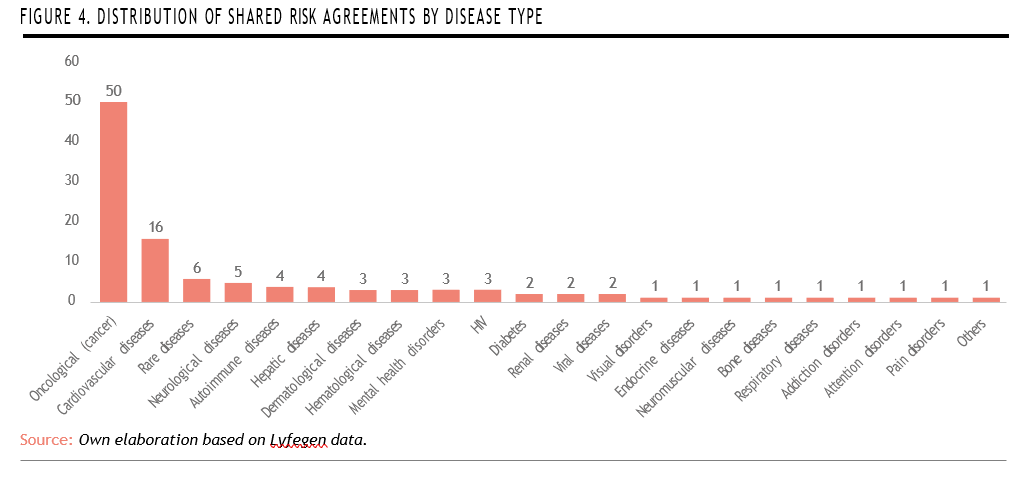

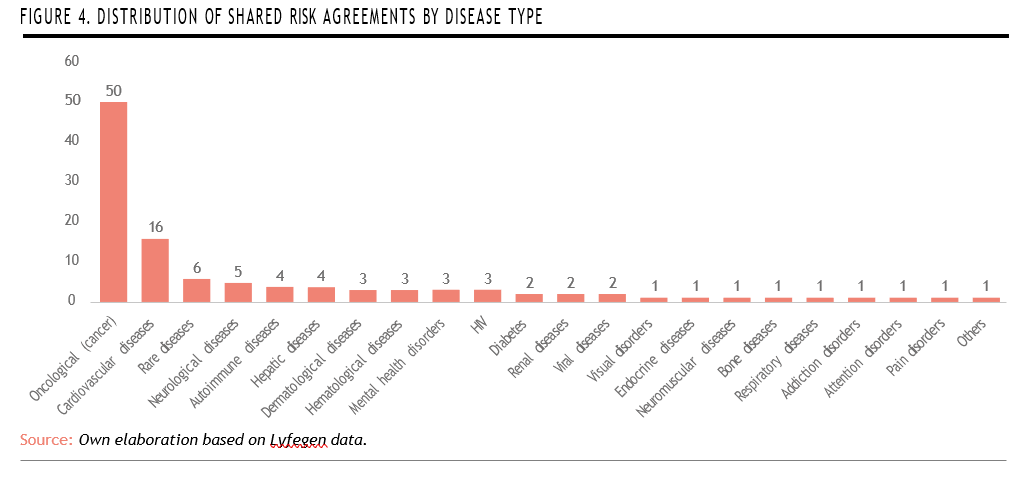

A disease-specific analysis reveals a strong concentration of shared risk agreements in severe or chronic conditions, with oncological diseases (cancer) leading by a significant margin (50 agreements, representing 45% of the total), followed by cardiovascular diseases with 16 agreements. Rare diseases rank third, with 6 agreements, indicating a growing—though still limited— interest in applying innovative payment models to this highly complex therapeutic area.

Despite their relatively high placement, the number of agreements for rare diseases remains modest compared to their clinical relevance and economic impact, suggesting room for further expansion of outcome-based and risksharing strategies in this domain (Figure 4).

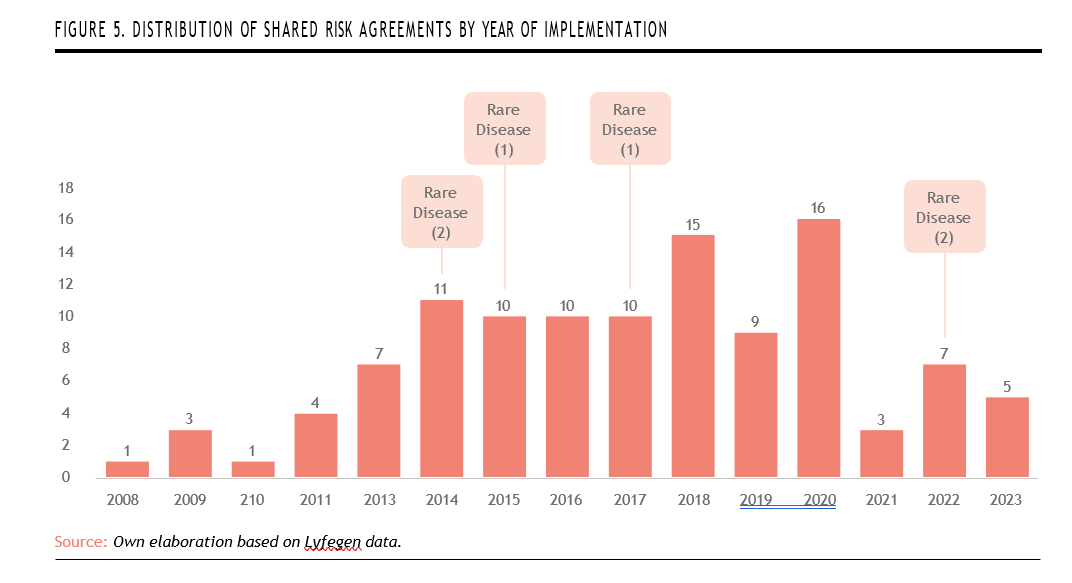

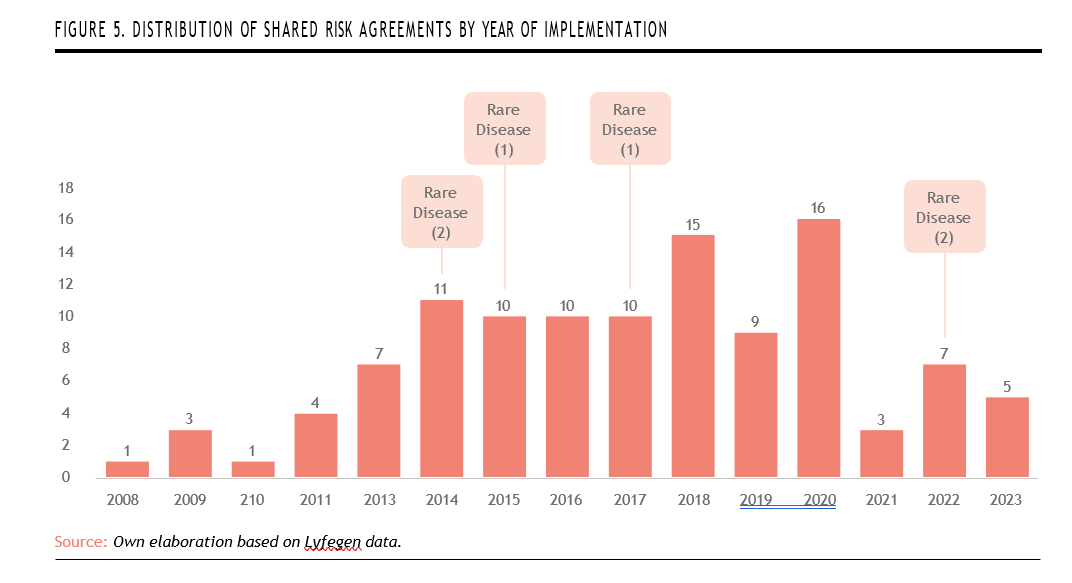

A higher frequency of agreements is also observed starting from 2013,reaching a peak in 2020 with 16 agreements. Rare diseases appear sporadically throughout the implementation timeline. The first recorded rare disease agreements emerged in 2014 with two agreements, followed by one agreement each in 2015 and 2017. The most recent activity occurred in 2022, with another two agreements. This distribution suggests a cautious but sustained inclusion of rare diseases within shared risk frameworks. However, their intermittent presence also reflects ongoing challenges in integrating complex, high-uncertainty therapies into structured outcome-based models on a consistent basis (Figure 5).

TECHNOLOGICAL INTEGRATION IN OBP AGREEMENTS

As healthcare systems continue to evolve in the digital age, the integration of smart technologies into OBp models is becoming increasingly common—and necessary. Tools such as artificial intelligence, electronic health records, and automated platforms are transforming how treatments are assessed and reimbursed, making it possible to link payments directly to real-world clinical outcomes. This shift not only enhances the feasibility of performance-based models but also raises expectations for greater accountability and transparency in healthcare financing.

In the following section, we will examine how specific technologies are being applied to OBP models, focusing on practical examples that illustrate their role in streamlining implementation, improving data collection, and supporting evidence-based decision-making.

Valtermed

Valtermed is a centralized digital platform developed by the Spanish National Health System to assess the real-world effectiveness of pharmaceutical treatments. Its main purpose is to collect and analyze patient outcomes from the use of new and often high-cost medicines, helping improve treatment safety and effectiveness while supporting decisions related to value-based reimbursement and resource allocation.

The system gathers detailed patient-level data—covering clincal, therapeutic, and administrative aspects—which allows healthcare providers to monitor each patient’s condition from the beginning of treatment and track their progress over time. The data collected are guided by pharmaco-clinical protocols, which are created through collaboration among expert working groups recognized by national healthcare authorities18.

Data entry is carried out by health- care professionals through a secure, web-based tool that is connected to regional health information systems. This integration ensures that information is consistently recorded and shared across the public health- care network17,18.

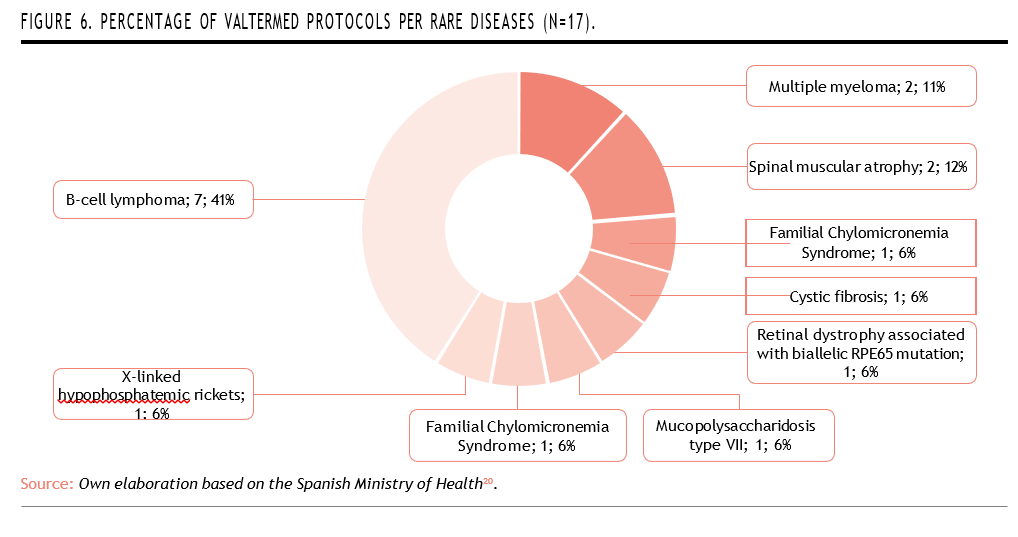

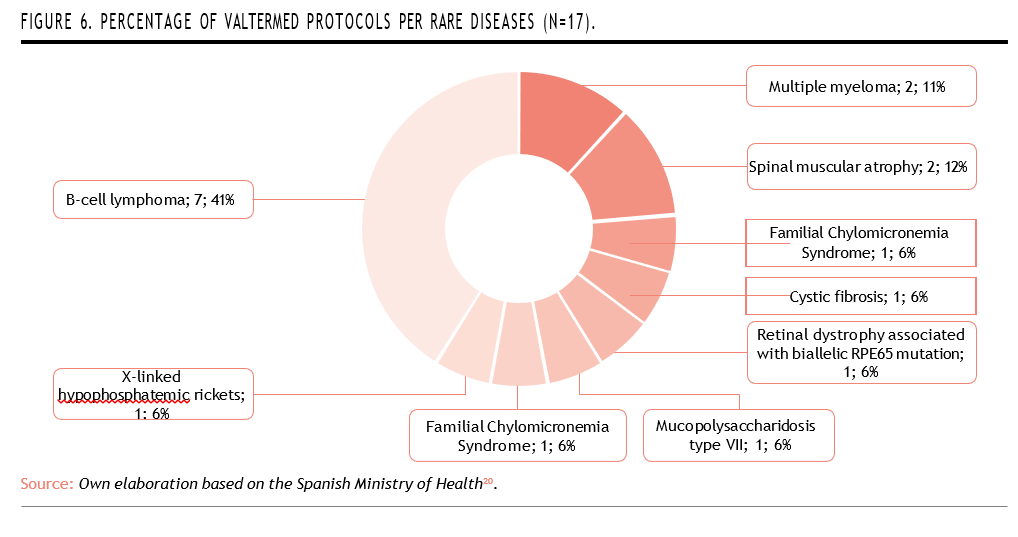

Valtermed plays an especially important role in the field of rare diseases, where reliable data are often scarce19. Out of the 21 active protocols currently in place within the system, 17 focus specifically on rare disease treatments, reinforcing its value in generating real-world evidence for complex, low-prevalence conditions (Figure 6)20.

One of the first structured examples of a technology-enabled OBP model in Spain is the case of Luxturna. This agreement illustrates that it is possible to tie drug reimbursement directly to clinical outcomes— even in the context of rare diseases where uncertainty is high. It also sets a precedent for future models by using the Valtermed platform as the central tool for monitoring and validating patient results21.

One of the first structured examples of a technology-enabled OBP model in Spain is the case of Luxturna. This agreement illustrates that it is possible to tie drug reimbursement directly to clinical outcomes— even in the context of rare diseases where uncertainty is high. It also sets a precedent for future models by using the Valtermed platform as the central tool for monitoring and validating patient results21.

Voretigene neparvovec (Luxturna) is a gene therapy developed to treat both children and adults with vision loss caused by a hereditary retinal dystrophy linked to biallelic mutations in the RPE65 gene, provided that patients have enough viable retinal cells to benefit from the therapy22.

Through Valtermed, clinical out comes for patients receiving Luxturna are tracked across hospitals within the Spanish National Health System. Payment to the manufacturer (Novartis) is conditional on the patient showing measurable improvements in visual function at specific time points—such as 30, 90, and 365 days after treatment. If these predefined clinical goals are not achieved, a portion of the treatment cost must be reimbursed by the manufacturer23.

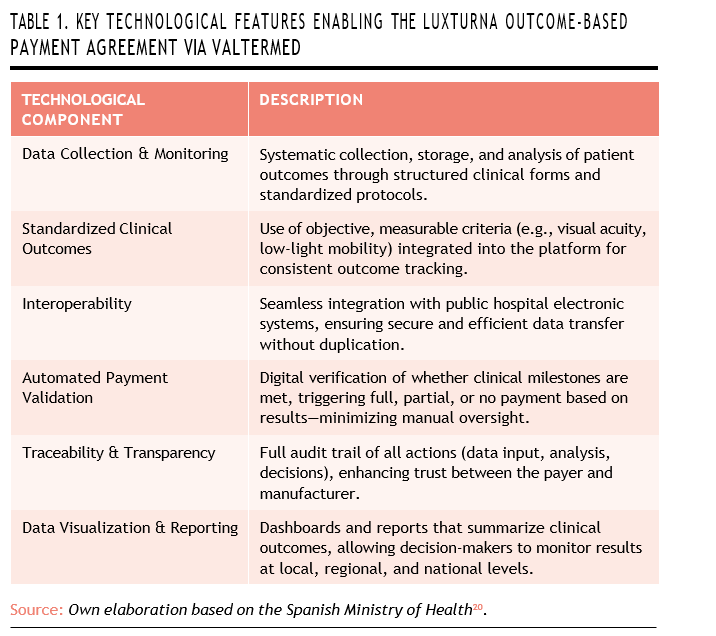

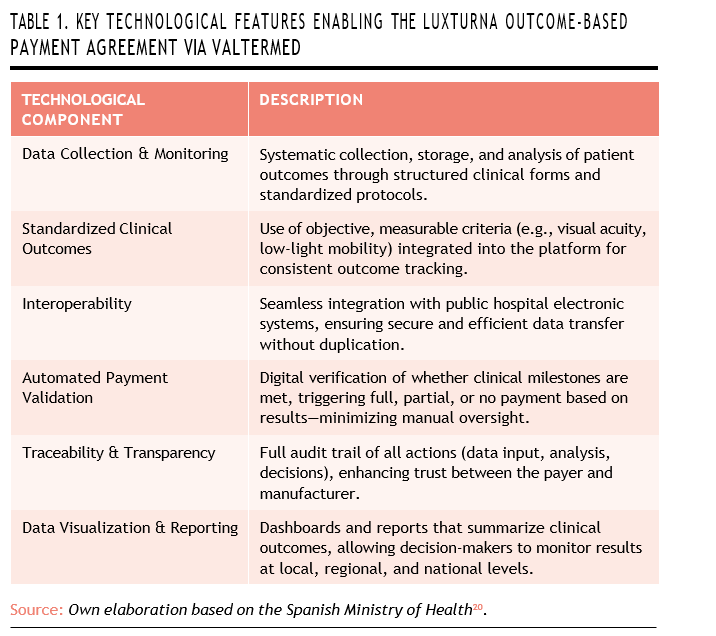

Several technological components made the Luxturna OBP agreement possible, with the Valtermed plat- form at its core. Valtermed enables the systematic collection, storage, and analysis of patient outcomes for high-impact therapies. It relies on structured clinical forms, standardized measurement protocols, and long-term patient monitoring to ensure consistency and reliability in data gathering.

A key feature of the agreement is the standardization of clinical outcomes. To make the contract verifiable, objective and measura- ble criteria—such as visual acuity tests or assessments of mobility in low-light conditions—were clearly defined. These outcomes are fully integrated into the digital platform, allowing for automated comparisons and centralized reporting across different hospitals.

Valtermed is also designed to work seamlessly with the electronic systems used in public hospitals. This interoperability ensures that clinical data can be securely transferred without duplicating records or disrupting existing workflows, making the process more efficient for healthcare professionals.

Another important element is the automatic validation of payment milestones. The platform determi- nes whether the clinical outcomes specified in the agreement have been met, and based on this, it triggers either full reimbursement, partial payment, or a refund. This process is fully embedded within the digital workflow, reducing administrative workload and minimizing room for subjective interpretation.

In addition, the platform provides full traceability and transparency. Every step—from data entry to outcome analysis and payment decisions—is digitally recorded and auditable. This transparency strengthens trust between the healthcare payer (Spain’s National Health System) and the manufacturer (Novartis).

Finally, Valtermed offers powerful tools for analysis and visualization. It produces dashboards and summary reports for decision-makers at both regional and national levels, making it easier to track the progress of clinical outcomes over time and across institutions (Table 1).

Lyfegen

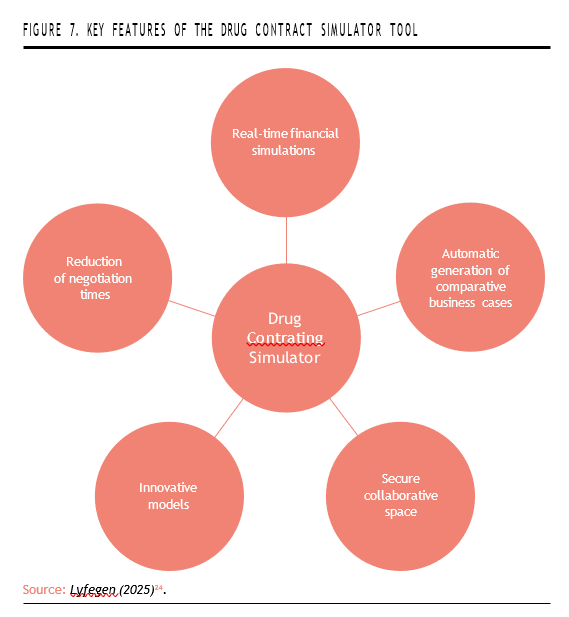

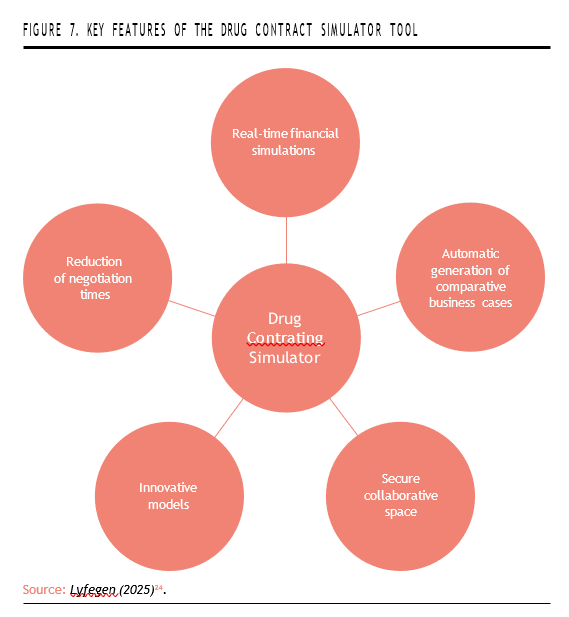

Founded in 2018 and based in Basel, Switzerland, Lyfegen16 is a health technology company focused on transforming how healthcare systems manage the cost and value of inno- vative treatments. Its main product, the Lyfegen Drug Contracting Simu- lator, is currently used in more than 40 countries by insurers, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies. The platform supports the design and management of value-based reimbursement agreements by allowing users to simulate various pricing models, including outcome-based and performance-based contracts. Through this tool, both payers and manufacturers can evaluate the financial and clinical impact of therapies and negotiate agreements more efficiently and transparently24.

The Lyfegen platform offers several key features that support more agile and evidence-informed negotiations. It enables real-time financial simulations across a variety of scenarios, incorporating variables such as price, treatment volume, patient adherence, taxes, and more. Users can automatically generate com- parative business cases—such as best-case, base-case, and worst-case scenarios—which help guide strategic decisions and improve the quality of negotiations. The platform also provides a secure and collaborative digital workspace, allowing both global and local teams to work together with full version control and access permissions. Its focus on innovative reimbursement models—ranging from value- and outcome-based pricing to installment plans and performance guarantees—makes it especially well-suited for high-cost and complex therapies like gene therapies and rare diseases. According to the company, Lyfegen can reduce negotiation times by up to 18%, significantly cutting down on manual calculations and administrative workload (Figure 7)24.

Overall, the Lyfegen platform streamlines the negotiation process by making it more agile, transparent, and data-driven. It reduces reliance on complex manual calculations, supports smooth collaboration among international teams, and speeds up decision-making through access to a rich library of real-world agreements and reference models. This combination of features allows stakeholders to compare options quickly and accu- rately assess the financial impact of each proposed contract, ultimately leading to more effective and informed agreements.

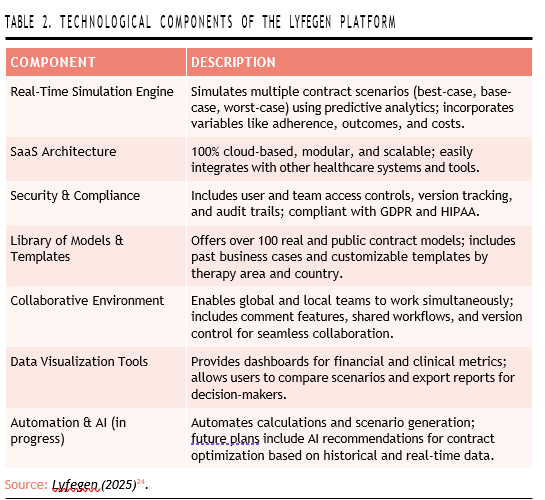

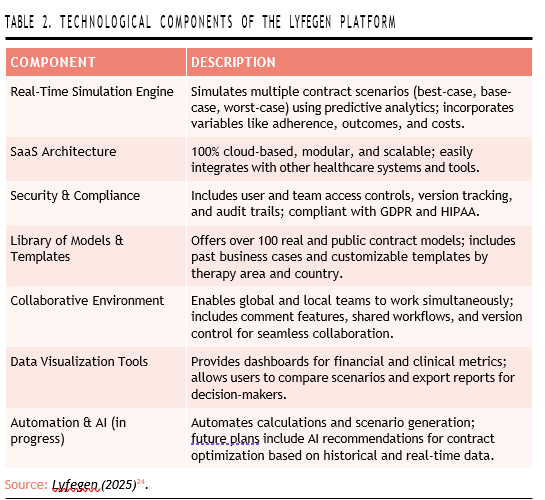

Technological Components of the Platform

The Lyfegen platform is built around a set of advanced technological components that enable flexible, data-rich contracting. At its core is a realtime simulation engine that can automatically calculate multiple contract scenarios using financial algorithms and predictive analytics. These simulations take into account a wide range of variables, including patient adherence, treatment duration, taxes, clinical outcomes (in the case of outcome-based models), and cost-effectiveness thresholds24.

As a fully cloud-based software-as-a-service (SaaS) platform, Lyfegen is accessible from anywhere and offers a modular, scalable design that allows for easy integration with other digital tools in the healthcare ecosystem.

Security is another critical component: the platform includes user-level access control, team- and project-based permissions, full version tracking, and audit trails. It is also designed to comply with major data protection regulations such as GDPR and HIPAA24.

To support contract customization and benchmarking, Lyfegen provides access to a rich library of over 100 real-world and public contract models. These include historical business cases and customizable templates tailored to different therapies and national contexts. Collaboration is also central to the platform’s functionality: teams across geographies can work together simultaneously within the platform, communicate through built-in comment and review features, and follow a shared digital workflow for approvals and negotiations24.

Interactive data visualization tools are embedded into the system to support decision-making. Users can access dynamic dashboards showing the financial impact and outcome metrics of different the- rapies, compare scenarios directly, and export reports for presentation to internal or external committees24.

Finally, automation is a growing part of the platform’s development roadmap. Many tasks—such as scenario generation and financial calculations—are already automated, and the company is exploring the integration of artificial intelligence to recommend optimal contract models based on historical data and current negotiation parameters (Table 2)24.

mHealth apps

The use of mobile health applications (mHealth apps) has grown rapidly in recent years, with more than 350,000 apps currently available on the market25. These digital tools offer a broad range of functions that can significantly enhance patient care, particularly by allowing healthcare professionals to access clinical data in real time. Key features of these apps include symptom tracking, monito- ring of treatment outcomes, and the recording of medication adherence26. This ability to collect structured, time-sensitive patient data positions mHealth apps as promising tools to support OBP models.

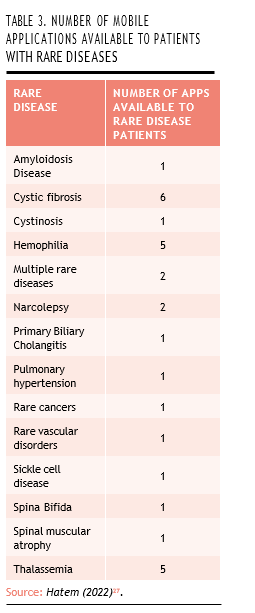

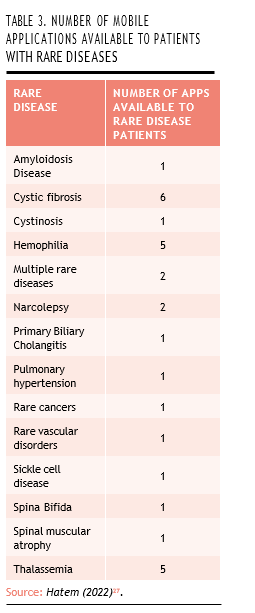

Their potential is especially relevant in the context of rare diseases, where patient numbers are small and clinical follow-up can be highly individualized. Many patients with rare conditions already rely on mobile apps for disease management, offering a natural entry point for integrating these technologies into OBP frameworks. A study conducted by Hatem (2022) identified 29 mobile applications specifically designed for 14 rare diseases or disease groups. Among the most frequently addressed conditions were cystic fibrosis, hemophilia, and thalassemia, reflecting both the clinical need and the potential for digital innovation in these areas (Table 3)27.

Some mobile health applications have been developed specifically for patients with rare diseases, offering tailored functionalities that support both self-management and clinical oversight. One example is the Fabry App28, designed for individuals living with Fabry disease—a rare, X-linked lysosomal storage disorder caused by mutations in the GLA gene. This genetic defect leads to a deficiency of the enzyme alpha-galactosidase A, resul- ting in the accumulation of a substan- ce called globotriaosylceramide (GL-3 or Gb3) in various tissues. Over time, this buildup can cause a wide range of complications, including neurological, kidney, heart, inner ear, and cerebrovascular problems29,30.

The Fabry App provides patients with a user-friendly platform to log daily health information, including symptoms and medication intake. The data entered by the patient is securely transmitted to a password-protected online portal, where healthcare professionals can access and review the information. This continuous, remote monitoring helps clinicians track disease progression and adjust care more effectively, supporting the kind of real-world evidence collection that is crucial for OBP models28.

Another notable example is Haemoassist®, a mobile application designed to support self-management for individuals with hemophilia. This digital tool allows patients to record treatment administrations, bleeding episodes, and other clinically relevant information in real time using an intuitive interface. By facilitating structured and timely data entry, the app helps improve adherence to therapy and enables more accurate clinical monitoring31-33.

Haemoassist® is also linked to a web based portal, which aggregates patient-reported data and presents it through statistical sum- maries and visual dashboards. This setup allows healthcare profes- sionals to easily review trends and make infored treatment decisions based on real-world insights31-33.

Given their functionality, mobile health applications offer valuable opportunities to support OBP models. Their ability to capture reliable, patient-level data makes them ideal tools for tracking clinical outcomes, and their integration into OBP frameworks could be strengthened through closer collaboration between payers and pharmaceutical companies.

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN IMPLEMENTING TECHNOLOGY IN OBP AGREEMENTS

Implementing OBP models, particularly in the context of rare diseases, demands a coordinated infrastruc- ture capable of capturing robust real world data, managing financial flows over time, and aligning stake- holder objectives. However, despite the promise of tools such as Valtermed, Lyfegen, and mHealth apps and several others, several technical, organizational, and regulatory challenges persist—alongside sig- nificant opportunities for innovation and improvement.

Data Quality and Integration

High-quality, interoperable data systems lie at the heart of OBP frameworks. Although Valtermed demonstrates interoperability with regional hospital systems, broader data integration remains limited. Fragmented electronic health records and inconsistent data standards across regions hinder comprehensive tracking of clinical outcomes. Additionally, registering longitudinal data in mHealth apps poses challenges in patient adherence and data completeness; inconsistent usage can generate incomplete datasets, undermining the reliability of performance-linked payments34.

Administrative Burden

OBP agreements impose significant administrative overhead, including data collection, outcome validation, and contractual reconciliation over time. As reported in studies of managed entry agreements for advanced therapies, these burdens can reduce feasibility and scalability35. The complexity is exacer- bated when spread over several years, requiring multiyear financial tracking often incompatible with existing 12-month healthcare budgeting cycles. The result is potential resistance from providers and payers faced with manual processes and contractual complexity.

Payment Architecture and Financial Flows

Traditional healthcare financing sys- tems are structured around upfront or lowest-cost budgeting; shifting to spread or outcome-adjusted pay- ments presents logistical hurdles. Governance questions arise around who purchases the therapy and how outcomes trigger payments—processes that must integrate clinical systems and financial ledgers in real time. To resolve this, newer models propose centralized payer procurement— rather than provider-led invoicing— with payers distributing treatment costs based on validated outcomes, similar to approaches taken with Lux- turna. However, this necessitates new governance frameworks and accounting adaptations35.

Contractual and Governance Frameworks

Achieving stakeholder alignment on outcomes, timelines, and termination triggers is a perennial challenge. Literature emphasizes the difficulty of reaching consensus on clinical endpoints, data collection processes, and optimal payment duration, especially in the context of high-cost rare-disease therapies. Additionally, explicit contracts must address potential adverse selection, where payers or manufacturers might influence patient inclusion based on expected outcomes. Multi-stakeholder governance structures—such as independent steering committees—are essential to maintain transparency and oversight.

Regulatory and Legal Constraints

OBP models must adhere to regulations governing data privacy, healthcare reimbursement, and accounting. The European GDPR restricts the use of individual patient data unless properly anonymized. Bud get cycle constraints and accrual accounting rules may treat installment payments differently from lumpsum purchases, complicating implementation at the national level. Harmonizing these frameworks across jurisdictions remains an ongoing challenge.

Long-Term Agreements vs. Annual Budget Cycles

One of the most pressing challenges in implementing OBP models is the misalignment between long term payment structures and the short term nature of hospital bud geting. Most public healthcare ins- titutions operate on annual budget cycles, which are not well suited to manage multi-year or outcome-de- pendent payments that may unfold over extended periods. This issue becomes even more complex in cases where clinical outcomes will only be available far into the future—for example, some gene or cell therapies require up to 12 years of follow-up to confirm their full the rapeutic value. In such cases, hos- pitals and payers face significant uncertainty about how to account for potential future liabilities, how to record these contracts on their financi al statements, and how to plan for reimbursement beyond the typical one-year horizon. Without specific legal or accounting mechanisms to address this temporal mismatch, long-term OBP contracts may encounter ins- titutional resistance or fail to scale effectively within existing public finance frameworks.

Opportunities and Enablers

Despite these challenges, techno- logical advances present numerous opportunities:

- Automated, integrated data platforms—such as Valtermed and mHealth apps—can reduce manual workload, enhance data quality, and facilitate near real-time outcome tracking.

- Centralized digital negotiation tools, exemplified by Lyfegen, can streamline agreement design, facilitate benchmarking using a global library of contracts, and reduce negotiation timelines.

- Emerging payment models, such as outcome-linked annuity systems, spread financial risk and align incentives over time.

- Governed registries and external audit structures can help build trust and compliance, offering visible oversight while addressing privacy and governance require-

- Cross-country collaboration and standard-setting bodies can promote shared data standards, aligned endpoints, and streamlined implementation pathways.

In conclusion, the integration of technology into OBP models represents a significant opportunity to improve access, transparency, and sustainability in the financing of orphan drugs. As demonstrated through the use of platforms such as Valtermed in Spain and Lyfegen internationally, digital tools are increasingly capable of addressing the uncertainty and complexity that often surround rare disease treatments. These technologies enable the systematic collection of real-world outcomes, support the design and monitoring of risk-sharing agreements, and enhance collaboration among stakeholders.

However, this evolution is not without its challenges. Issues related to data interoperability, administrative burden, legal frameworks, and financial structures continue to limit the scalability of OBP models. Yet, as healthcare systems gain experience and invest in digital infrastructure, many of these barriers are becoming more manageable. Furthermore, the growing use of mobile health applications offers a promising frontier for patient engagement and long- term monitoring, especially in rare diseases where data is traditionally scarce.

Ultimately, realizing the full poten- tial of OBP in rare diseases will require continued cross-sector collaboration, regulatory flexibility, and investment in scalable digital ecosystems. Technology is not the solution in itself, but it is a critical enabler of a more adaptive, patient-centered model of drug reimbursement.

References

- Implementing Value-Based Health Care in Europe [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://eithealth. eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Implementing-Va- lue-Based-Healthcare-In-Europe_web-4.pdf

- Khalil H, Ameen M, Davies C, Liu C. Implementing value-ba- sed healthcare: a scoping review of key elements, outco- mes, and challenges for sustainable healthcare systems. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1514098.

- Freitag A, Iheanacho I. Rare Diseases and Orphan Drugs. Where are We Now? [Internet]. Available from: https:// www.evidera.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/A05_ RareDiseases_EFFall20.pdf

- Andreu P, Karam J, Child C, Chiesi G, Cioffi The Burden of Rare Diseases: An Economic Evaluation. 2022;

- Villa F, Di Filippo A, Pierantozzi A, Genazzani A, Addis A, Trifirò G, et al. Orphan Drug Prices and Epidemiology of Rare Diseases: A Cross-Sectional Study in Italy in the Years 2014–2019. Front Med [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 4];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/ medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.820757/full

- Hanchard MS. Debates over orphan drug pricing: a meta-na- rrative literature Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2025;20(1):107.

- Pijeira Perez Y, Wood E, Hughes Costs of orphan me- dicinal products: longitudinal analysis of expenditure in Wales. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023;18:342.

- Facey KM, Espin J, Kent E, Link A, Nicod E, O’Leary A, et Implementing Outcomes-Based Managed Entry Agree- ments for Rare Disease Treatments: Nusinersen and Tisa- genlecleucel. PharmacoEconomics. 2021;39(9):1021–44.

- Langley PC. Formulary Submissions: Value Claims, Protocols and Outcomes Based Contracting in Rare Innov Pharm. 2022;13(3):10.24926/iip.v13i3.5020.

- Garrison LP, Towse A, Briggs A, de Pouvourville G, Grue- ger J, Mohr PE, et Performance-based risk-sharing arrangements-good practices for design, implementation, and evaluation: report of the ISPOR good practices for performance-based risk-sharing arrangements task force. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2013;16(5):703–19.

- Wenzl M, Chapman S. Performance-based managed entry agreements for new medicines in OECD countries and EU member states [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 3]. Avai- lable from: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/ performance-based-managed-entry-agreements-for- new-medicines-in-oecd-countries-and-eu-member- states_6e5e4c0f-en.html

- Dévora C, Abdalla F, Zozaya Modelos de financiación en enfermedades raras: de donde venimos y hacia donde vamos. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 3];7(2). Available from: https:// weber.org.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/nR-13- Vol-7-num-2-2022-WEB.pdf

- Gonçalves Value-based pricing for advanced therapy medicinal products: emerging affordability solutions. Eur J Health Econ. 2022;23(2):155–63.

- Bohm N, Bermingham S, Grimsey Jones F, Gonçalves-Brad- ley DC, Diamantopoulos A, Burton JR, et al. The Challenges of Outcomes-Based Contract Implementation for Medici- nes in Europe. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022;40(1):13–29.

- Carlson JJ, Sullivan SD, Garrison LP, Neumann PJ, Veenstra Linking payment to health outcomes: a taxonomy and examination of performance-based reimbursement sche- mes between healthcare payers and manufacturers. Health Policy Amst Neth. 2010;96(3):179–90.

- About Lyfegen | Innovating Healthcare Solutions [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 2]. Available from: https:// www.lyfegen.com/about-us

- Jørgensen J, Hanna E, Kefalas P. Outcomes-based reimbur- sement for gene therapies in practice: the experience of recently launched CAR-T cell therapies in major European countries. J Mark Access Health 2020;8(1):1715536.

- Ministerio de sanidad, consumo y bienestar social, Secretaría general de sanidad y consumo, Dirección general de cartera bàsica de servicios del SNS y farmacia. Preguntas y repuestas frecuentes sobre el sistema de información para determinar el valor terapéutico en la pràctica clínica real de los medica- mentos de alto impacto sanitario y econoómico en el sistema nacional de salud (Valtermed) [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/ farmacia/infoMedicamentos/valtermed/docs/VALTER- pdf

- Arganda C. EERR: Valtermed y riesgo compartido para re- ducir incertidumbres | @diariofarma [Internet]. diariofarma. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 23]. Available from: https://diario- com/2019/02/13/eerr-valtermed-y-riesgo-com- partido-para-reducir-incertidumbres

- Ministerio de Ministerio de Sanidad – Áreas – VAL- TERMED: Resultados en salud [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/ farmacia/infoMedicamentos/valtermed/home.htm

- Ministry of Health. Pharmacoclinical Protocol For The Use Of Voretigene Neparvovec In The Treatment Of Retinal Dystrophy Due To Biallelic Rpe65 Mutation In The Natio- nal Health System [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://

www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/farmacia/infoMedicamen- tos/valtermed/docs/20210504_I_Protocolo_voreti- gen_neparvovec_distrofia_retiniana.pdf

- European Medices EPAR: Luxturna [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Jun 25]. Available from: https://www.ema. europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/luxturna

- Iglesias-López C, Agustí A, Vallano A, Obach M. Financing and Reimbursement of Approved Advanced Therapies in Several European Countries. Value Health J Int Soc Pharma- coeconomics Outcomes Res. 2023;26(6):841–53.

- Pharmaceutical Simulation | Accelerate Negotia- tions with Lyfegen [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 2]. Availa- ble from: https://www.lyfegen.com/pharma/simulator

- Wells C, Spry C. An Overview of Smartphone Apps: CADTH Horizon Scan [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 2]. (CADTH Horizon Scans). Available from: http://www.ncbi. nih.gov/books/NBK595384/

- Collado-Borrell R, Escudero-Vilaplana V, Narrillos-Moraza Á, Villanueva-Bueno C, Herranz-Alonso A, Sanjurjo-Sáez

- Patient-reported outcomes and mobile applications. A review of their impact on patients’ health outcomes. Farm Hosp. 2022;46(3):173–81.

- Hatem S, Long JC, Best S, Fehlberg Z, Nic Giolla Easpaig B, Braithwaite Mobile Apps for People With Rare Diseases: Review and Quality Assessment Using Mobile App Rating Scale. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(7):e36691.

- D’Amore S, Mckie M, Fahey A, Bleloch D, Grillo G, Hughes M, et al. Fabry App: the value of a portable tech-

nology in recording day-to-day patient monitored infor- mation in patients with Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024;19:13.

- Germain Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:30.

- Schiffmann R, Fuller M, Clarke LA, Aerts JMFG. Is it Fabry disease? Genet 2016;18(12):1181–5.

- Haemoassist | Pfizer España | Pfizer España [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.pfizer.es/salud/ sitios-web-y-aplicaciones/haemoassist

- Redacción. Una aplicación facilita el seguimiento en he- mofilia [Internet]. Diario de Sevilla. 2015 [cited 2025 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.diariodesevilla.es/ sociedad/aplicacion-facilita-seguimiento-hemofi- html

- Haemoassist, nueva app para los pacientes con hemofilia [Internet]. COCEMFE. 2015 [cited 2025 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.cocemfe.es/informa- te/noticias/haemoassist-nueva-app-para-los-pacien- tes-con-hemofilia/

- Tomassy J, Khatri U, Perez L. HTA252 Analyzing Critical Dri- vers for Success in the Implementation of Outcome-Based Agreements to Manage Clinical Uncertainty Risks in Value Health. 2022;25(12):S345.

- Michelsen S, Nachi S, Van Dyck W, Simoens S, Huys I. Barriers and Opportunities for Implementation of Outcome-Based Spread Payments for High-Cost, One-Shot Curative Thera- Front Pharmacol [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Jul 2];11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/ pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2020.594446/full

When focusing specifically on rare diseases, the data reveals a more limited adoption of OBP agreements across select countries. Italy stands out as the most active, having implemented two agree- ments related to rare diseases, one in 2022 and another in 2014; howe- ver, these represented only 4% of the total OBP agreements imple- mented in the country during the period. Germany follows with one rare disease agreement initiated in 2022. Among the group of «other countries,» three nations have each introduced a rare disease-focused OBP agreement: Ireland (2017), Egypt (2015), and Albania (2014). While these numbers are modest relative to total OBP activity, they highlight growing international willingness to apply performance-based approaches in the high-uncertainty context of rare disease treatments (Figure 2).

When focusing specifically on rare diseases, the data reveals a more limited adoption of OBP agreements across select countries. Italy stands out as the most active, having implemented two agree- ments related to rare diseases, one in 2022 and another in 2014; howe- ver, these represented only 4% of the total OBP agreements imple- mented in the country during the period. Germany follows with one rare disease agreement initiated in 2022. Among the group of «other countries,» three nations have each introduced a rare disease-focused OBP agreement: Ireland (2017), Egypt (2015), and Albania (2014). While these numbers are modest relative to total OBP activity, they highlight growing international willingness to apply performance-based approaches in the high-uncertainty context of rare disease treatments (Figure 2).

One of the first structured examples of a technology-enabled OBP model in Spain is the case of Luxturna. This agreement illustrates that it is possible to tie drug reimbursement directly to clinical outcomes— even in the context of rare diseases where uncertainty is high. It also sets a precedent for future models by using the Valtermed platform as the central tool for monitoring and validating patient results21.

One of the first structured examples of a technology-enabled OBP model in Spain is the case of Luxturna. This agreement illustrates that it is possible to tie drug reimbursement directly to clinical outcomes— even in the context of rare diseases where uncertainty is high. It also sets a precedent for future models by using the Valtermed platform as the central tool for monitoring and validating patient results21.